5. The Gentleness of Dust.

But first: actuarial prediction, narcissism, furious contempt and mess and solipsism, sexual revolutions, gingernuts and guilt.

Good morning, Person, says Richard Dickson from the doorway.

Good morning, Dick Richardson. I trust you slept well?

Your trust is well-placed. As you know, I am a good sleeper.

We’re in the bedroom. George is still lying in his flat-out-like-a-lizard-drinking posture and snoring very quietly. Out the open door to the veranda I can see a sliver of dawn illuminating Pellmell’s big sign on the adjacent wall that tells the world that there’s an actuary nearby to predict the future by occult means so as to inform people’s decisions about random acts of god, nature, and terrible people. The sign doesn’t show a portrait of a crystal ball though, just a clean-jawed bright-eyed young woman smiling triumphantly over another victory over fate. As Pellmell is neither clean-jawed or young, must be her daughter, whom I’ve never met, but still, she might exist.

Oorrrow? asks Dick from his threshhold station, what’s for breakfast?

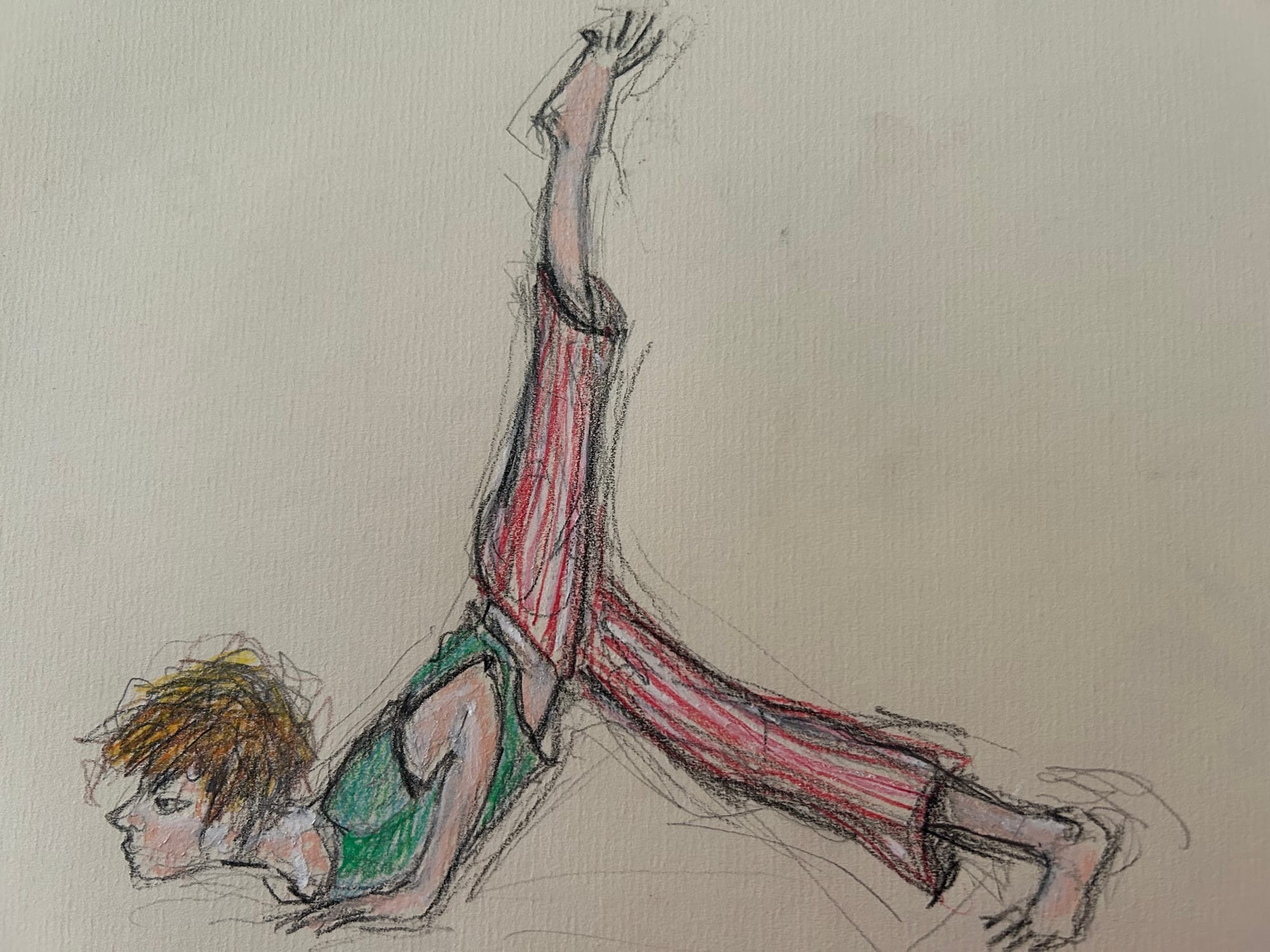

I get up carefully. It’s rare for George to sleep in and when he’s awake he moves very fast and with such gusto it’s unnerving to both Richard and me. But now he’s a battery recovering his charge. Being lovingly attached to a person of extreme high energy is worrying because you can get apprehensive if they do something as simple as have a lie-in. (Why aren’t you awake and zooming about? What’s wrong?) I breathe deeply for a minute or two, then shake myself quite hard, stretch upwards then roll down to execute a quick locust pose.

That was never a locust, observes Richard.

Stay in your lane Dick, you’re a cat, not a short-horned grass-hopper.

I go outside to stand on my head for a little while.

Richard approaches and brushes his furry flank across my upside-down nose, then sits down next to my right ear. But breakfast, Person? he says.

Dickson, just a sec.

It’s not always easy to interpret subtle shades of mood in a cat’s regard, but it is clear that I am now receiving a gaze of disconsolate resignation. But I wanted to complete my inversion. So, together, the disconsolate cat and his person look out over the bay. We see a big, rangy dog walking alongside that statuesque beauty from the cafe, focus of Samson’s intense admiration. I can tell it’s her even at this distance; nobody else has that hair. In the morning sun it looks like her head’s on fire. She’s joined by a little pixie of a man. Ah, Samson, you don’t waste any time. Now they’re inclined towards each other, talking earnestly. Interesting.

I set down one leg, then the other, get upright and make my way along the veranda to the kitchen, go to the fridge and inspect its contents. Richard, I note, is looking around, giving the room a measured appraisal before saying, Perhaps, like George, I should’ve stayed asleep a bit longer. Given you a chance to clean up some of the mess we were discussing only recently with AF.

I look around. I hate mess, though I’m very good at it.

You do mess like I do sleep, the cat mentions helpfully as I heave a haunch of wildebeest from the fridge for his delectation. Roll it out onto the veranda.

I make tea. I hear the shower running—George has survived the night. Whew.

I’m particularly keen on George’s survival because this is the first time I’ve been involved with a man whose sweetness isn’t forced, whose curiosity about the world is enduringly lively, who is generous in his appraisal of other people… in short, the sort of man I wouldn’t have looked at twice when I was young, being attracted only to self-absorbed ones who, it always emerged after a while, had been attracted to me for qualities which over time they had come to find insupportable. By then, often enough, I’d come to find them insufferable. In hindsight I see these men shared certain attributes: an apparently gentle diffidence that was actually boredom—because other people talking was of little interest to them—yet capable of flattery when necessary and exhibiting the charms of confidence and intelligence that, I would later realise, never extended beyond their own narrow interests.

They were men—more than three, fewer than seven—whose vanity required the bolstering of woman-as-helpmeet or ornament. Aided by the seductiveness of their early blandishments and my own lust I fell easily enough for these tricks of the light, and for a time I’d somehow convince myself that my weakness, abetted by a talent for self-immolation, were strength and bravery. But now, no more. No more needy, feeble-spirited men with glossy patinas brought to their high shine by the ministrations of female polishing cloths. No more captivating charmers. If I’m to have a man, then I’ll take George.

I sip my tea in the doorway as he rushes by and bolts down the stairs, saying something. I pick up a noun, a verb, an adjective, plus another doubling as an adverb: ferry, run, late, later.

Richard takes a break from his breakfast as he always does, so as to savour it properly, and after brushing himself briefly against my leg to say thanks for the haunch, jumps up onto the couch to attend to another layer of felting. I’m left to my own devices, whatever those might be. A smart phone or a stupid radio maybe. Why not a ruler, that’s a device, or a clock, a thermometer, a dipstick. Yes, I could set about measuring things with my devices. Length, time, heat, depth. Not a very tricky avoidance technique.

But begin to tidy I must, and I do. Though it’s not a peaceful ‘making order’ thing, it’s more just stomping about and muttering. Sweep floor, swab fingerprints off fridge door—ah ha, floor/door rhymes! Look inside, why not? Sniff milk. Mmm. Not off! HA! Sweep up these grains of kitty litter I’m crushing under my bare feet; wipe down the benchtop because I just spilt that milk I was sniffing. Up the corridor to make the bed, hooray! I’m just like Julie Andrews in The Sound of Music, might just get out the old Singer and run up a few dresses out of the curtains! Back to the living area and open those envelopes piling up on the bookcase, the envelopes with the windows.

Oh, no!

Oh no what? says AF, squeezing himself out from a congeries of compacted meningeal membranes.

I draw the line at looking at bills, AF. That’s not tidying, it’s admin.

Gadzooks, says AF. Them’s the breaks.

I sweep the envelopes into a box file indecisively balanced on a bookcase and watch it wobble then topple, spilling its contents new and old onto the floor. AF is disgusted. What’s got into you? he says in a tone just like my mother’s—a statement framed as a question but without a question mark. Probably Samson’s mother said it too, though who knows what her motivations were, her being anastrophic and all, as he recently explained. Meanwhile, this morning, a generation later, when I’m older than my mother was when she didn’t know what had got into me, the ‘question’ is still a statement. Mum’s gone but AF is here to say it for her.

My mother had a beautiful sense of the absurd and a sweet, feline smile, and she could be sharp with my brother and me. Though not with Bernie, my handsome, charismatic father. At least not soon enough. (Oh yes, she was a slow learner too.) Maybe the change started not long before Pieman (a nickname my brother never shook, poor boy) and I finished school; I was seventeen (off interstate to art school); he was fifteen (off interstate to be a jackaroo). We witnessed her ironic remarks that showed her scorn for Bern’s magisterial pronouncements of rock-solid certainties, of his condescending dismissals of her opinions. If only she’d started earlier. Nobody should force themselves to bear the humiliation of contempt, and by the time I returned to visit the family home for the first time since I’d left—about six months later—contempt was mutual, though probably complicated with other things, like familiarity, admiration—or the ghost of it—some stubborn affection, walnuts, god I don’t know. Maybe they stayed together for us, though if I’d been asked, I would’ve recommended divorce.

But AF is on my case again: Tidying is tidying, You. Everyone has to do it—clean up after themselves, obviously.

But the thing is, it’s every day, AF! I hate it and my hatred is visceral.

Yes, yes, I know, diddums. You’ve mentioned electric eels and whatnot. Maybe you could get yourself a treat later.

AF’s last suggestion now causes the eels to rear up in my brain, hissing wildly through bared fangs...

… so I throw down the tea towel I’d just grabbed and clenched in a white-knuckled fist. No, AF! Don’t give me the treats line! I mean, I’m seriously sick of this ‘be kind to yourself’ bilge drivel crapacious garbage! ‘Buy yourself something because you’re worth it, they say…

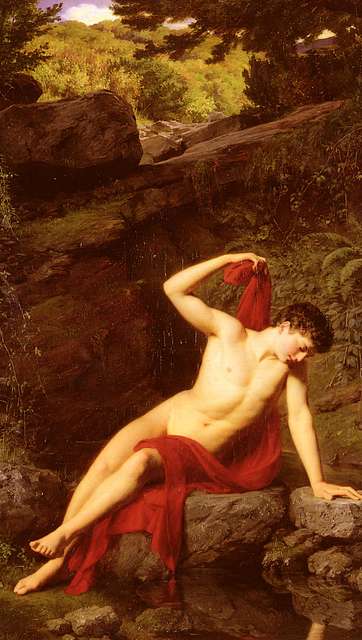

… those windy pissy marketing nincompoops… and all that ‘self-care’, ‘self-love’ we’re supposed to be doing, it used to be called egotism, all grist for the mill of those marketeers everywhere you look working on our pathetic little vanities and urging us to get more stuff to feed them so that multinationals can smile over the stats worked out by the people who add things up and draw conclusions come the end of the financial year, and what about those self-help gurus, yeah, what about them, all queuing up to dispense life advice, wanting us to buy their books flogging tips on how to show yourself compassion (self-compassion—argle bargle—compassion is meant to be fellow feeling!), love, love me me do!, spawning litters of little narcissists all staring into our own ponds fringed by reeds, our yearning over impossible self-confidence self-worth self-love echoing off the cliff faces all around, the grim cliff-faces looking down all disdainful and mineral with no feelings, oh dear, they don’t care, poor me.

So we leave our narrow valleys, our little ponds, and go out into the world carrying with us a sense of injury—those mean cliff faces!—because we know we’re the centre of the universe. Then while walking along the street—we’re in the city now, AF, keep up—watching a video of Tony Robbins on our phones, we bump into someone else who’s also the centre-of-the-universe, and another and another, all feeling righteous about self-care … oh god, it’s crowded in here, cos we’re ALL Universe-Centre.

Revelation! Phheough. I do the thing with the air puffing out the cheeks and leaving the lips pneumatically.

Look, you monstermouth, says AF. People aren’t just telling each other consoling fables. There’s value in some of that stuff, and what’s wrong with comfort anyway? And I wasn’t suggesting a week in Noosa, just a gingernut with your tea. Jeez Louise.

Richard is now regarding me thoughtfully from the couch. Then he jumps up and exquisitely picks his way through the snowdrift of bills. He says, I do understand your dislike of housework and of capitalism’s aggressive pushing of luxury items and self-help literature upon the populace, Person, and I agree that your irritation with the overuse of so-called ‘self-care’ is warranted. I mean, if that sort of loving attention was directed outwards towards the world, towards other people on it, then we’d all be covered.

I think of the lovely lines of Simone Weil: ‘We have to try and cure our thoughts by attention… turn our minds towards the good.’ It’s very hard. I sigh in physical and moral fatigue. I sit. Richard, I say, you are a very generous-hearted cat.

Richard replies, I’m not particularly generous, just practical. If people listened more to cats there’d be less war.

That’s a leap, opines AF, rolling his eyes liquidly behind my own (horrid sensation).

Not really, AF, Dick replies coolly. I’ll let you think about it yourself if you want. Incidentally, I wonder how Samson’s going with the Goddess of the Precarious Hair? I saw them talking again yesterday. Their heads were together, a curly one and a lustrous one of several shades from deep russet to pale blonde and an enviable silver streak. They looked intimate.

Intimate? enquires AF. Easily mistaken for conspiratorial.

What would they be conspiring about? I ask. Samson and the… how did he put it the other day?… ‘explosion of delicious lubriciousness’?

Sexual revolutions, obviously, replies AF.

Although it’s not possible to see my Annoying Friend, his voice sounds like it’s coming from a mouth whose cheeks are stiffened by irritation. He’s probably still pissed off about the ‘treat’ thing. Or being condescended to by a cat.

That’s pretty dramatic, opines Dr Richard Dickson. Revolutions, I mean.

Not necessarily, AF rejoins, with a certain level of pomp, as if a chorus of trumpets was trumpeting him. Revolutions can start fairly quietly, Cat. The wheel of change cycles slowly, gathering momentum as it progresses while crushing the bodies that have fallen to whatever cause set it in motion. And this goddess with the hair like nesting tigers would have lots of bodies left behind in her progression towards her next phase, I’d say.

Would you, AF?

I would, Puss. The beginning of Samson’s and her revolution could be something as simple as working out where next to meet, or how to conceal their affair from her husband.

But do we know they’re definitely having a Thing, then? And is she married? asks Dick.

I leave them to it and start collecting the scattered letters. Then I ‘treat’ myself to a gingernut with my tea. And what am I doing, anyway, complaining about having stuff to clear up and look after? Whinging about letters that probably contain bills which show how much in the way of services I can actually afford to pay for? So I feel guilty. My complaints aren’t just redundant, they’re feeble. And wrong. First world problems, yes, yes. Guilt guilt self-loathing. And I know what you’ll say to that, AF, about my judgemental nature starting with myself and then extending to the rest of the imperfect population; cranky, me, with a deep dearthness at my centre like a black hole and getting all pernickety over housework like one of those ladies who runs a boarding house for ‘young spinsters’ in 19th-century Bath. But just hold off for a minute, can you.

AF doesn’t deign to reply. In the silence of his replylessness it occurs to me that ‘just hold off for a minute, can you’ is another statement that should be a question—my Mum was a super rhetorician and now so am I! Sorry, Mum, I’m being mean, I think. Hey, AF, this is meanness that I’m doing, probably?

…

AF?

What?

I suppose it’s a kind of …

Yes, I heard you the first time and yes, obviously it’s meanness, You.

That wasn’t a question, I say.

Then don’t put a question mark at the end. And, by the way, even if you hadn’t put an actual question mark at the end then your phrasing still implied a question mark.

You’re not the boss of my punctuation, I tell him pathetically.

At the back of my head I can feel AF rolling his eyes again. It’s a sort of rocking and plunging sound, unpleasantly moist. I roll mine back at him, making him wobble on his perch at the edge of my right eyeball’s ciliary body. Ha.

By the way, You, the paragraph you wrote a minute ago wasn’t your finest—first you renege and have a biscuit with your tea, then you start with the pathetic guilt-and-privilege line as if mouthing those words can make you less guilty or privileged, which isn’t just ineffectual, but morally shabby, as is the self-pity that comes next.

But I meant to infer moral shabbiness, it was intentional, thank you, so stet.

Stet you too.

I wipe down the countertop. I look up and note dust on the shelf above. I don’t wipe it away. I don’t mind dust, in fact as I’ve said before, I like it quite a lot. It’s a counterpoint to vibrant, lively, living memory, just a gentle primordial residue made of desiccated insect-matter and skin that’s got tired and fallen off and crumbled. To dust.