TALES FROM THE END OF THE WORLD

Pre-apocalyptic thoughts and stories, deep and shallow, of sea level goings-on by myself, an invisible Annoying Friend, and the excellent Dick Richardson.

We three consider a number of questions such as, Is it possible to fall in hate as it is to fall in love? Is a view from above more or less edifying than a view from below? Who actually is the beautiful Leonora? How good is it to scream in your car? How do the words we choose to use affect how we look at things? Why is it that certain people do all in their power to bring on Armageddon?

(But look, regarding that last question: I’m not a wild-eyed doomsayer. I’m just a person who reads, who lives in a village, who considers people, things and ideas I find fascinating or lovely or enraging, and who is, 1. horrified that life on this planet—such a gorgeous unaccountable fluke!—is being trashed by the stupefying rapaciousness and deep fuckwittage of pig-ignorant megalomaniacs and all those bound to them by need or fear, and 2. a person with uncertain concentrational abilities who is intent on loving what I have, in fact and in memory.)

I’m compelled to write these little stories... which, please note, may be read in any order, but will make the best sense if read consecutively, ok?

So, memoir, reflection, invention… here we go…

1. Pathetic Fallacy:

Welcome to my home and to some reflections on weather and memories set in two very warm places, with some careful consideration of how best to describe these and other things properly.

Morning. Sun sliding up over the edge of the tree-line on the other side of the bay, which I can see clearly from here because I’ve set my desk in the doorway, a big wide sliding door, all metal and glass. Such materials, when allied with blocks of concrete can be brutish and oppressive, too often forming massive slabby shelves that overshadow the streets and their passing pigeons and humans and dogs; they groon and groan their statements of authority below the level of human hearing on slow, infrasonic waves get into your head. They upset the balance of my invisible Annoying Friend, who spends quite a bit of time in the vicinity of my auditory nerve.

But this particular building has been made with care, the deep awning obviates the need for aircon in summer, it’s only a couple of storeys high, and has substituted ruthless concrete for more sympathetic materials, wood and brick. No, this building is not the product of the expedient greed of real estate developers. It is not after blood. It demonstrates sympathy with the street, which remains sunny in the sun and rainy in the rain, its rights of way uncontested, its creatures unmolested.

I push the doors open and they slide comfortably, companionably, admitting eddies of air like water lively with fish. From where I sit I can see the pots of herbs, marjoram, parsley, something with big red flowers that sowed itself on the veranda. Dick Richardson pauses on the threshold next to my desk for the requisite beat that cat protocol demands, looks over his shoulder in case he’s leaving something better than he’s about to find if he proceeds, decides to enter. As he passes me he says Hmmrrhh eah, which translates as, You have a caterpillar problem in your variegated sorrel.

Thank you, Dick. I’ll look into it.

It rained overnight again, as it did the night before and the night before that. Malcontented drizzle, thick and slow. The blues of gumtrees across the road that ought to be crackling with humour by this time of year have raindrops dropping from their pointed tips in slo-mo, and the creek’s painted the bay the colour of weak tea. After a while the café people open up shop and voices filter up to me from downstairs. Someone says, What is it with this weather!

(Please note, dear reader: I wrote this first draft in January, and January used to be reliably hot in this southern country. It’s just that it took months for me to work up the nerve to start posting.)

I run a finger down the bridge of my nose, roughened with keratoses,

as I think of the hottest places I’ve experienced. Giza—which I’ve visited a couple of times, once during a North African summer, and where, one afternoon, I saw the serenely dead face of a king in a tomb. I also saw a scarab beetle standing on her forearms and pushing a ball of dung back towards her home with her hind feet, and later, an eagle riding a thermal below where I sat, high above the plains, on the back of a compliant donkey called Mustafa. Probably the very hottest day I’ve experienced. The second hottest was Adelaide, a small Australian city between hills and the Southern Ocean. In Adelaide, summer heat can get so dry your skin peels away even if you never go outside. I didn’t. It was just, I came, I saw, I peeled. I moved there to go to art school just as soon as I finished high school, and there I discovered reggae, sex, Patti Smith, shoplifting, and how to live on lentilsonionscarrots.

Dick, now napping on the edge of the desk, opens one eye and says kindly, But Person, I think you’ll find these things may have existed before you, so strictly speaking, you did not ‘discover’ them.

You’re right, I answer. But I was a teenager then and therefore a monstrous solipsist, so stet, alright?

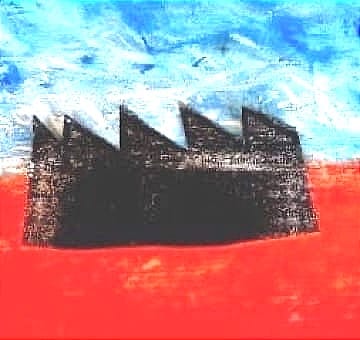

For a while I had a job at a factory well outside the city, a large rectangular building of corrugated iron set in land cleared of life. I remember the perpetually falling and self-replenishing veils of dust inside, its texture and its scent, metallic and chalky, like disappointment. From the bus stop I’d cross the concrete courtyard towards the iron roof serrated like blades of a bread-knife cutting into the insanely blue sky.

Insanely blue? says Dick. I suspect you’re transferring your own youthful vexations onto the elements.

A pathetic fallacy, adds AF, my very Annoying Friend, he who lives invisibly but vigorously in this or that mental cranny and interrupts my thoughts pretty regularly. Dickson might be sophistic at times, blunt at others, but I always feel a certain amount of goodwill coming from the cat, and he’s also wise, but AF can be heartless in his pedantry. I mean, did he really have to italicise ‘pathetic’?

So now I’m thinking, pathetic: failed, tragic; sad yet stupid. Fallacy: something that’s wrong. A false belief. Like anthropomorphising cats or getting responses when talking to yourself.

Sorry, Person, but plenty agree with AF, mentions Dick. Poets romanticising the countryside by paralleling human moods with nature’s…

…is fallacious and a tragic failure of expression, intrudes AF, smirking. I can feel the smirk curling around the back of my right maxillary sinus. Nature doesn’t have ‘moods’, he adds. And metaphor interferes with facts.

I sit back down in my chair at my desk and stare at the screen, determinedly cutting out AF’s static.

In the late afternoon at the factory we’d take a break for a bite to eat. We’d bring sandwiches or cheese and small boxes of sultanas. Once somebody brought a little camp stove and fried a couple of eggs, sunny side up, I remember, with yolks luminous in the pre-twilight, gleamishly bulging from their whites like myxamatotic eyeballs. The sun was slanting down almost horizontally, making some of us squint. We ate on a patch of grass near the cyclone wire fence through which could be seen a lot of flat inhospitable land.

Only, no. It might be flat—but inhospitable? Here, now, sitting at my desk so many years in the future, I’m googling—no, wrong, using Duckduckgo I must be ducking—that place in the Adelaide Plains where I’d worked in the factory, and I find no mention of inhospitability or hospitality. Then I think about related concepts, like the reciprocal demands etiquette makes on visitors and hosts, the pretty basic things that English settler-colonists neglected to observe in this country, like being polite enough not to drive your truck through someone’s fireplace then build concrete constructions with immense doors of callous steel over the top of it. Showing some interest in the way the hosts have arranged things instead, asking intelligent questions whose answers you might learn from and that you do actually want to ask because you’re curious.

But the visitors have been utterly incurious and vulgar and cruel, and they weren’t even guests. They were gatecrashers who came and saw and trashed the joint. And have been trashing it ever since cos growth is good, heheh, if its money that’s doing the growing, not plants or human wisdom or appreciation of the ages of wind and sun it takes for a mountain to become a plain filled with round-leaf wattle and eucalyptus and flax lilies and honey myrtle and sweet little twiggy daisy bushes and kangaroos, emus, koalas...

When the whistle blew it meant that it was time to return to work so we packed up our stuff and began to walk back towards our iron-roofed shed with its interior of solid noise and dust. The twilight had arrived—it moves fast in this part of the world—and had reached its phase of deep electric blue, a colour more like a sensation that fills your heart with dread or yearning depending on your nature. The effect lasts just a short while before it fizzles. I worked on a production line. It was profoundly boring. Only, no, again. It was existentially boring. My job was to put a screw into the back of each speedometer that came to me along the conveyor belt. But the thing is, the speedos were for exercise bikes. So I was helping people to gauge the speed of a bicycle that would never go anywhere! When this thought occurred to me I felt so sad.

So very sad. But it doesn’t do to sob on a production line (check her out - so desperate for the next screw hahaha) so I put up my hand; the overseer came over and I told him I needed the loo, then I went outside and lit up a cigarette. I heard a kookaburra laughing hysterically, then another, then total kookophony!

It’s just a territorial thing.

I know it’s just a territorial thing, AF! God. But look, the sound enters your ears and travels down to your diaphragm and lifts your heart and gives it a little shake, polishes up its tired ventricles, then pops it down again into its pericardial nest. The newly lightened heart laughs along with the kookas. Or cries. Or cries and laughs.

I get up from the desk and go out onto the veranda. Do some yoga stretches. Down dog. Cat pose.

That was never a cat pose, Dick says, in a tone that’s affectionate but unavoidably superior.

Possibly not, Richard Dickson. Just a bit of poetic allusion, human people respond to that sort of thing.

AF chimes in: That heart of yours you just mentioned—showing off your corporeality as usual—it’s just a muscle, you know. You can’t take it out and polish its ventricles.

I don’t answer, hoping he’ll go away.

The pericardium is a fluid-filled sac, he adds.

I need to get away from AF so I go down to the other end of the veranda and in through the living-room–kitchen door, which is the same as the study door I’ve just left, metal but not unkind. Put the kettle on, leaves in the pot. Dickson Cat comes too. He likes the kitchen. Together we watch the kettle. Despite rumours to the contrary I trust it will boil, eventually.

But AF’s still with us, of course, and he’s still at me. Now he’s saying, Poems and made-up stories confuse the issue. Give me a fact any day. Something you can sink your teeth into. You’d appreciate that, wouldn’t you, Puss?

Richard looks in the direction of AF’s voice, sees nothing but me, of course, decides that he isn’t keen on such informality from invisible people at the moment.

Puss, indeed, he says as he sashays away, his bumhole winking derisively.

During the brief conflict between my two companions I’ve poured the hot water into the pot and carried it, along with a cup with a bit of milk in it, back along the veranda to my desk. I call up a file with research I’d done on words to support the case for poetry and metaphor. I read that in 1650 Cornelius Agrippa wrote, ‘the power of… verses is so great that it is believed they are able to subvert almost all nature.’

I feel AF’s eyeballs rolling heavenwards. The sound of invisibly rolling eyeballs inside my head is discombobulating.

Language has ‘the power to construct reality’, I say. Then I add, a bit smugly: Bourdieu, 1979.

Another philosopher, sighs AF. But language ain’t bricks.

In the ’90s we’ve got people talking about metaphor as ‘capable of creating realities’. Transformative!

Yeah well whatever, scoffs AF.

Don’t be churlish.

I’m not a churl, nor a villein, nor a peasant, nor any other kind of indentured labourer, current or medieval.

Just trying out an adjective for effect. Admit it, AF, doesn’t ‘churlish’ give an impression of how you feel at the moment? Like, say, a person made sullen because they’re losing an argument?

Ok, ok. I’ll concede that round to you.

That round? Are you alluding to our field of verbal conflict as a boxing ring, AF? Is that a metaphor?

Shut up, You.